India

Travels with Angel

The folks who make the Voyage-Air folding guitar have an Owner’s Club on their website and I was asked to contribute my experiences. That led to my written reflections on the place that each guitar that’s come into my life represented a place, a time and a memory, and my realization that I had never really selected my own instrument till a turning point that started with a dream. The article is at their website (link below), and I’ve reproduced it here with a few changes, edits and upgrades. Link to the article at the Voyage-Air site: http://www.voyageairguitar.com/owners-club/featured-owner/505

Here’s my expanded article with more pix:

Travels with Angel

Travels with Angel – My Journey to the Voyage-Air

By Rev. Nettie M. Spiwack

Jim Wolcott at Voyage-Air asked me to write a few words about my experiences with their folding guitar, that little marvel of which I was an early adopter.

For a musician, every instrument has its unique place in your history.

One night back in 2001 I had a dream about a guitar. As I came awake, the verses of Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Old Beat Up Guitar” were in my mind:

She traveled with me always, through the alleys and the bars

The songs I sang and the friends I knew were a part of that guitar…

Jerry Jeff called his guitar “Angel,” after someone drew one on the top of it. Finding, losing and then finding her again in his travels features prominently in that song he recorded in 1972, and which I hadn’t thought of in a few decades.

Well, a traveling man has trouble holding on to all he owns

And in those years of traveling that guitar fell by the road

Then one night in New Mexico, I stumbled into a bar

And there lay Angel smiling at me on that old beat up guitar.

The dream was a message. I was about to go out to play music for a retreat in California, and I knew it was time to go find my Angel.

I had played many guitars in my life by that time, but in truth, not one of them had I selected and bought myself.

I started playing folk guitar early, in a wonderful setting that was right out of a cliché. I was nine years old; it was summer at Camp Johnny Appleseed where my mother was working that year in the camp office. With mom’s brown Favilla nylon-string guitar—bought in aspiration of her learning to play it, as my parents were part of the Hootenanny generation—I attended a group class, sitting on a porch in the Catskills and learned Woody Guthrie’s “Rambling Boy” with three whole chords in the key of A.

Mom’s brown Favilla became my guitar, the one I toted around in its cracked chipboard case—a glorified cardboard box, really—to group and then private lessons. Carrying my guitar didn’t represent too many difficulties because first of all, I was young, both the guitar and the case were light, no airplanes were involved, and no one around me then knew anything about humidity control, or if it was wise to take a guitar in a cardboard box on the NYC subways in winter. Soon, renditions of Go Tell Aunt Rhody gave way to the music of the Beatles and James Taylor and Crosby Stills & Nash.

By my years at the High School of Music & Art, I graduated to dad’s huge Harmony Sovereign grand concert. That guitar remains one of the biggest I’ve ever seen to this day. (Quantity, however, should never be confused with quality). Dad really never learned to play more than “You Are My Sunshine,” and turning his guitar over to me caused him no pain. It too, had a chipboard case, was a lot heavier to lug around, and I can still feel the indentation in my hand from the metal rings on the side of the plastic handle.

In the height of the folksinger/songwriter era, numerous other guitars had joined the family as my siblings and I played: my brother’s Guild 12-string, his Gretsch electric, my sister’s La Madrilena classical guitar, and a ¾ version of the same which my mother was determined to, this time, learn to play. (She didn’t.) There was always something to play and often someone playing it. I spent most of those years working out Joni Mitchell’s repertoire and figuring out an occasional open tuning for playing her songs.

I married a man with a Martin D-28, the gold standard of a serious player at the time. (I married up!) He was trying to make it as a performer when we met, though that dream eventually got put aside, and both of us stopped playing for a long stretch. When years later, we parted, he was kind enough to let me keep his Martin on extended loan, for by that time I was starting my career in spiritual music, and guitar was once again front and center in my life.

The D-28 had its legendary sound, not to mention cache, but it had some drawbacks. First, it had tough action, and my hands had a touch of arthritis, which made bar chords on the very rounded neck painful to hold. And then, there was the case. This guitar had the heavy hardshell case with weighty gravitas to match its content. The problem was, I was now in my 40’s and lugging it around to gatherings near and far, and worse, through long airport corridors and onto planes, got harder and harder. Not to mention that my ex was not enthused about my traveling with it.

After that Jerry Jeff dream, I knew it was time to return the Martin to her rightful owner and to go find my own Angel to travel with me.

That first Angel was the Larrivee Mahogany Orchestra Model, which fit me and my hands to a “t”; which I loved and which I lugged with its big heavy hard case through airports, across the USA, and even through India. Angel was later joined by a Taylor 12-string, whose case is so heavy that she’s rarely left my living room.

But as Angel and I made our way around over the next eight years I noticed that I wasn’t getting any younger, there’s never a roadie when you need one, the airport corridors got longer, and the airplanes fuller and fuller.

I needed another Angel. One I could travel with but that could still produce worthy sound. I was heading back to Brazil, to a retreat and healing center where I often end up leading music for hundreds of people.

I scoured music stores and the internet for travel guitars. It seemed that not much had changed in the years since I’d last looked. The choices were some sticks with strings, or perhaps a parlor-sized guitar. I had just about settled on a Baby Taylor, when I did one last search. And up popped the aptly named website, TakeYourGuitar.com. When I saw the Voyage-Air’s folding neck, I thought: it’s too good to be true! Then I realized, it’s like rolling luggage: once it was invented, you can’t imagine that no one had figured that one out before.

But how could I buy a guitar off of a website, never having played it or heard it?

Jim Wolcott patiently answered my many questions with great enthusiasm. His passion for the Voyage-Air persuaded me. My family and friends got together and gifted one of the Songwriter series to me for my birthday.

Welcome to the era of Angel II.

I was happily surprised by everything about the guitar…how good it sounded, how easy the action was, how well my hands could manage the (mercifully flatter) neck. And how light it was! Truth be told, I have many purses and totes that are far heavier!

Since 2009, this Voyage-Air guitar has traveled twice to India, several times to Brazil, and on countless trips around the USA. It’s been on every type of airplane, and by zipping off the computer case, I even managed to squeeze it under the seat on a small flight from Madurai to Bangalore when it looked like I might have to check it.

My Voyage-Air never fails to cause a stir. It’s still not widely known, and I’ve even had flight attendants ask me to open it so they could see it!

This summer in Brazil, a classical guitarist almost fell over himself when he saw me fold the neck down. He held it mesmerized, smiling, unable to believe the sound and the engineering.

My Larrivee, Angel I, now holds court in my house and steps out once in a while for local gigs. She’s enjoying her retirement, and truth be told, sometimes I look at her wistfully when I’m going on the road, thinking maybe this time I’ll take her. But Angel II always wins out.

Now she travels with me always, through the alleys and the bars

And the friends I make and the songs I write are a part of that guitar,

Some nights it is my pillow resting underneath the stars

Day and night I stay alive with that old beat up guitar.

Well, being a minister and all, I’m neither in alleys nor bars, and I’m more likely to be sleeping on a plane than under the stars. But the spirit of my Angel is the same to me as Jerry Jeff’s was to him, which he captured so beautifully in that song.

Jim and I talk about my upgrading, and maybe at some point I’ll welcome Angel III.

Till then, if you see me at an airport with my Voyage-Air, wave hi!

Rev. Nettie M. Spiwack

Interfaith Minister

about.me/nettiespiwack

revnettie.com

www.nettiespiwack.com

“That Old Beat Up Guitar” by Jerry Jeff Walker, from Jerry Jeff Walker, MCA-37004 1972.

Share this:

This entry was posted in Memoir, Stories from the Journey and tagged Celebrating Life Ministries, guitar, India, music, Soulfyre.

Namaste: Beholding & Projecting the Divine

On my first visit to India for a world diversity conference in 1997, I made friends with Marisa, an Indian woman who lived in Mumbai. Though she was Catholic, she was quite comfortable in the Hindu culture surrounding her. While sightseeing in the city, she took me to a temple that, if it wasn’t actually ancient, was in enough disrepair to qualify it as such.

We took our shoes off at the designated place in the outer courtyard. Like many entrances to Hindu temples, there was a statue out front. It was a bronze cow or bull, (I wasn’t sure), that had been worn shiny by countless hands touching it in reverence before entering the inner sanctum. Suspended over it was a bell.

“Come, let’s ring the bell, and let the gods know we are here,” she smiled, beckoning me to follow her example.

I kept looking at the shiny bronze cow, which in all its relaxed golden glory looked exactly like something Charlton Heston smashed with the original tablets of the Law in Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Ten Commandments”—just seconds before cartoon fire descended from heaven to consume all the “ye of little faith” crowd. (Those were top-of-the-line special effects back then, in the days before Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic.)

Despite my multi-cultural self, all my Jewish upbringing arose, and I couldn’t bring myself to touch that golden calf…er…cow…er…bull. (I did, however, follow Marisa into the temple).

Such is the power of cultural implants.

Judaism and Islam share something in common in this area: one is not supposed to make “graven images,” or represent God in any physical way. Art will express itself somehow, and from this proscription, you get the absolutely stunning Islamic calligraphy and decorative arts. (I think Jews were too busy being chased out of various countries around the world to develop a parallel artistic accomplishment on the same scale).

The point is, one didn’t paint pictures of God.

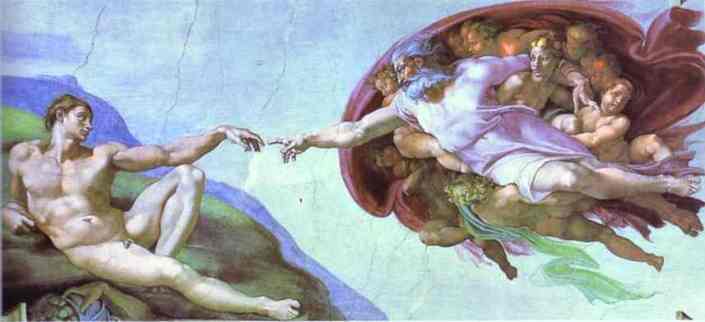

Someone failed to tell that to Michelangelo, however, and to countless other Christian artists before and after him. As we all know, the Catholic and Orthodox churches developed a sophisticated vocabulary of imagery precisely focused on statues and icons, thus giving us some of the greatest works of art in the Western world—which, as an art student all my young life, I imbibed with my milk and cookies (and later wine and cheese). Yet, like many outside that culture, worship that included images or even more disconcerting, statues, was beyond my understanding.

As I later got more and more immersed in teachings and culture of India, I got a different lens on the whole phenomenon. The Jungian writer, Robert A. Johnson, wrote in his biography Balancing Heaven & Earth:

Soul work, or inner work, takes place when something moves from the unconscious, where it began, into conscious awareness. The path is never straight and neat inside oneself, as if you could go to a library and do all your inner work there. Instead, when something is ready to move from the unconscious to the conscious, it needs a host or intermediary. Generally this intermediary is some person or thing.

In other words, a saint, guru, picture or statue.

Spiritually speaking, we need to project those divine qualities that are our birthright, that we carry within us, onto someone or something else.

Seen in a magnified way in another, it become easier for us to grow into those holy qualities, be they goodness, kindness or holiness itself. Indian tradition takes that a step further—a student literally worships the guru as God, with the understanding that the Guru is in fact a stand-in until the student can hold that Divine energy him/herself.

I attended a ritual in the city of Madurai on my last trip in 2009. At the end of the nine-day Dassera festival came an evening devoted to the women. As part of that holiday’s ritual, a young girl was dressed up as a goddess Parvati, and the older women fed and tended to her in a worshipful manner. The beautiful girl accepting the devotions of her elders was graceful and stunning. At the core of the ceremony was yet another variant of that all-encompassing Sanskrit greeting: Namaste: the God in me beholds the God in you.

When Mother Theresa was asked how she could embrace the most destitute and dying on the streets of Kolkata, she answered that when she looked at them, she saw Jesus. This, too, is the projection of the Divine.

In my home, I have little altars in most of the rooms. All around are pictures of Great Ones, statues, rocks; all triggers of remembrance. My daughter, when she was younger, used to complain that the house looked like a monastery, “with Bibles everywhere!” (The two Bibles I have were in my study.)

If we see the Divine outside ourselves enough, eventually we bring it home where it belongs, in the inner temple.

Where are your divine projections focused? Where do you think they come from? (People of different backgrounds see that divine seed differently.) How do you remember the sacred?

(If you are reading this on the Home Page, Comments links are at the bottom. If you are reading this as a single-entry page, the Comments link is at the top.)

Share this:

This entry was posted in Divinity, Memoir, Spirituality, Stories from the Journey and tagged Divine, God, goddesss, India, Namaste, Projection.